Inspiration can come from anywhere, and that's exactly what happened to me and gave me the idea for this post. I was talking to a fellow chronologist about his partial timeline of the cases of Sherlock Holmes, and the bulk of what you're about to read came to me in a flash during that conversation. It's something I had probably realized before, but never put into a structured thought. Well, now I will. It's time to categorize the different types of Sherlockian chronological timelines.

Now, Mr. O'Leary's list only includes twenty-six of the cases, but that is all he meant to include. He set out to cover just those cases. It's partial but complete. And it made me look at my collection a bit differently. There are six lists that I have asterisked (might not be a word) as "Incomplete chronology." But that's not actually a fair asterisking (possibly not a word, either). J. C.'s isn't "incomplete" - it's completely complete for what he set out to do. So, his becomes a partial (or as Brad Keefauver likes to call them - mini) chronology. I have two others that have cases listed as "Not decided" because they're mentioned in the chronological work, but the dates for them are, well, not decided. Technically these are "complete" even though they don't have dates for all of the original sixty cases. Thus, I need to be more certain about what divides the types. I need to update my filing system.

Questions have been asked lately about The Sherlockian Chronologist Guild coming up with a standard chronology for other Sherlockians to use for reference. I love the idea of being able to create that so people can use it, and for the Guild to have a place next the other "standard" chronology of William S. Baring-Gould. The problem is that it isn't that easy. There's so much indecision and/or division in the timelines that it's almost impossible to shape them into one viable thing. It is kind of possible to have a consensus about dates (Les Klinger did it some years ago and I updated it a couple of years after that), but often we're talking about a consensus of few people out of three dozen agreeing (or almost agreeing) on dates. It's not stable, and it's unfair to call it a consensus. As Mr. Keefauver says...

[T]he Canon is divided into parts: "Common Consensus Stories" (those with just one or two outliers on date), "Divided Consensus Stories" (those with a split that is basically two or three dates), and "No Consensus Stories."

At the latest 221B Con in Atlanta, GA, Brad introduced a clever way for the layperson to create their own timeline using the mostly-agreed-upon parts of The Canon and then filtering in the uncertain parts. It's fun, and I hope it spawns an actual chronology from one of the participants. (We'll discuss it further in a future post.) Perhaps, though, it will show others that there's almost nothing easy about constructing one of these things. That's why there's so few of them. And often the text is so dry to read that people will buy the book just to have it in their collection, or because they know the author and are just being kind, but never actually get through it.

So, what kinds of classifications are we talking about? It looks like there are four different types:

1. Full chronology - someone has went through the entire sixty original stories and placed a date on each one.

2. Partial (or mini) - only a part of the sixty have been chosen to date. Someone chose to focus only on a specific time range or set of circumstances.

3. Incomplete - for whatever reason a full timeline wasn't finished even though that was the goal.

4. Undecided - all of the cases are represented but some have dates that just can't be nailed down and are left as "undecided" even though the person tried.

Of all thirty-seven that I have, only two full ones have a specific date for every case, and only one partial and one incomplete are that way. All others have at least one ambiguous date like 'Spring 1888' or 'A January between 1883 - 1887'.

If I wanted to get really picky I could add:

5. True - one that tells us the logic and reasoning behind one's findings and is just about chronology.

6. Extended - one that has the logic and reasoning but is also a clearinghouse for all sorts of canonical problems.

7. Unrevealed - one doesn't tell us any of the logic at all, just dates.

8. Imitation - uses other people's dates entirely, or almost entirely, to create a timeline.

I discussed types #5 through #8 in a blog post in November 2017. You can read that here.

And though it doesn't actually count as a chronology, there is also:

9. Individual date - a lot of people have written great papers in which they discern the date for just one story, possibly more.

I don't know, however, where to draw the line between individual dates and a timeline. Is two a partial? I'll have to think about that one.

In connection with #9 I can even envision something like:

10. Associated (or Linked or Bracketed or Combined) - when a paper is about finding the date for one case, but it directly affects changing or dating another, and then those are discussed, as well.

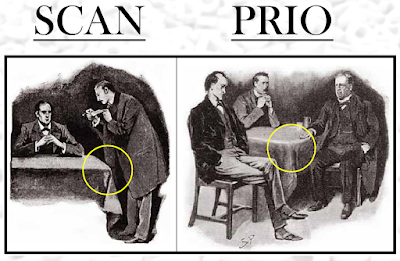

It brings me a lot of satisfaction when I get asked about a specific set of cases that someone is working on for a paper or presentation. People will ask about the 'Watson's marriages' cases, or the ones featuring murder, or the Lestrade appearances. There are so many options, and all are possible and accepted. I'm really waiting for a request for information that is as offhanded as the idea I came up with back in 2016 in my talk 'Misadventures In Chronology' in Minneapolis. It uses the dining table at 221b. See, sometimes the table in the illustrations has sharp corners, and other times it has rounded ones. Unless the residents owned both and changed them up on occasion then it seems that those cases - sharp vs. rounded - represent distinct, individual timelines. (I still think it's pretty clever, but I appear to be very alone with that opinion. Woe is me.)

So, as you can tell, this isn't just a cute little subset of a larger phenomenon - it's a demanding, worrisome, and studious endeavor. It takes time to pin down a date on a case that defies all efforts to do so. You have to decide what you are and are not going to ignore - wives, weather, past case references. Or you have to figure out what actual historical figure Holmes and/or Watson were trying to protect by hiding their identity. Frustration will set in when you try and determine if Watson simply misread his own handwriting, or if a snag was a typesetter's fault. You'll also find yourself reading cases with conflicting information, so you'll have to pick a side. And when you've finally got it all figured out you also have to make sure it fits into Holmes's 23-year career span, and then shoehorn Watson's 17-year partnership into that.

Perhaps it can be wrapped up best by a master in the literary field. Take it away, sir!

“You can approach the act...with nervousness, excitement, hopefulness, or even despair - the sense that you can never completely put on the page what's in your mind and heart. You can come to the act with your fists clenched and your eyes narrowed, ready to kick ass and take down names. You can come to it because you want a girl to marry you or because you want to change the world. Come to it any way but lightly. Let me say it again: you must not come lightly to the blank page.”

Stephen King in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

I really enjoy our time together. It's a pleasure to bring you my little rambles and rantings. I'll see you next month, and as always...thanks for reading.