I've said before that December can get a little hectic, and I was right. The holidays make any month nutty crazy, but this one seems to be the big kahuna. Still, I'm going to get at least one blog post in. It's my present to you...and you've earned it. You're welcome. So, let's blog about December itself, eh?

First, let's take a look at this from a chronological standpoint: December really doesn't have a lot of Canonical activity. Only five dates are listed in my database, which makes it the shortest month in those terms. February is next with eight. Seems the cooler months weren't a favorite of Watson's to write about. (If you believe the chronologists, that is.)

The five dates are:

The 4th, 7th, 8th, 19th, and 27th.

The cases discussed are: 'Charles Augustus Milverton' (CHAS), 'The Noble Bachelor' (NOBL), 'The Missing Three-Quarter' (MISS), 'The Beryl Coronet' (BERY), and of course 'The Blue Carbuncle' (BLUE). However, that's just for specific dates and stories.

Other less-precise dates are as follows:

Gavin Brend makes the list again with CHAS in December 1882.

***

Then he, Mike Ashley, Edgar W. Smith, and Aimee Shu like December 1889 for BLUE.

***

T. S. Blakeney will only go so far as to say "Christmas-time 1889" for BLUE, but I don't get the impression he always tried very hard to nail down exact dates.

***

Aimee Shu believes that BERY occurred in December of 1890, and also places MISS, and the yet-to-be-mentioned 'The Sussex Vampire' (SUSS), in December 1896.

***

Vincent Delay is the one who puts the 4th on the list above with CHAS, though he also likes December 1897 for 'The Abbey Grange' (ABBE), but doesn't give a specific date.

***

Five chronologists place a non-specific December 1897 on MISS - Roger Butters, Martin Dakin, June Thomson, Mike Ashley, and Gavin Brend.

***

The team of (Alan) Bradley & (William) Sarjeant place 'The Red Circle' (REDC) somewhere between 1902 and March 1903, so they may place that case in December. (Seems like a stretch, I know, but I like to be very thorough.)

***

Vincent Delay pops in again with 'The Three Gables' (3GAB) and says it fell in the range of July 1902 to November 1904, so there again it may have been December.

***

And Jean-Pierre Crauser says 'The Veiled Lodger' took place either in November or December 1902.

Now, any Sherlockian or Holmesian worth his/her salt knows that BLUE is the big story for December in our hobby. So far no one in the chronological community has been silly enough to place it anywhere else. And everyone agrees it was the 27th, but not everyone agrees on the year.

Here's the disagreements:

The Grand Master of most people's chronological usage, William S. Baring-Gould, places it in 1887. Until recently he was completely alone in this belief. I say recently because a newcomer, one Craig Janacek, places it there, too...although he admits on his blog that he is just agreeing with Baring-Gould.

***

Jean-Pierre Crauser, Vincent Delay, and Carey Cummings (who was planning on publishing a full chronology over time, but has yet to do so) says it was 1888.

***

Fourteen different timeliners place it in the (correct, in my opinion) year of 1889. (If you want the list of names, just email me.)

***

And poor old Jay Finley Christ is sitting out there all by himself with 1890.

So, even if they can't agree on anything else, they all agree that the case occurred in the very late 1880's, and two days after Christmas just like Watson said.

Anyway, to wrap this up in a big bow, let's break it down a bit and take another peak at what the life of a chronologists is like. This one month has ten different cases covering five different dates covering a range of twenty-two years (1882 - 1904) in which eleven are specifically listed.

I would like to point out that I have yet to add Mr. Paul Thomas Miller's newest chronology to the database. (December = hectic...remember?) I will be doing so soon, but after the holidays have passed and life goes back down to a slow simmer.

Thank you for sticking with me all the way until the end. I really enjoy when you do that. I'll try and get one more blog post out this month, but I can't promise it. I'll see you as soon as I can, and as always...thanks for reading.

Monday, December 23, 2019

Monday, November 25, 2019

The Newest Chronological Attempt?

Let's talk about chronology, shall we? Now, I know what you're thinking - "But, Historical Sherlock, haven't we been doing that all along?" Well, my lovelies, not every time. I occasionally take little side trips on these posts, but today it's all about the main theme here. There's a new chronology of The Canon, and we're going to examine it.

Paul Thomas Miller is a Holmesian from the U.K. I'm afraid I don't know a lot about him, but I do know he's an active member in our hobby. Recently he put out a book called Watson Does Not Lie, which is a chronology based on the idea that...well, here's what he says on the back of the book:

"I was told the creation of a Holmesian Chronology is practically a rite of passage. I was told once you have managed to make sense of the sixty stories you emerge a rookie no more. I was told it is a task that improves you and your understanding of The Canon.

I'm not so sure...

Too many chronologists resorted to claiming either Watson lied, or could not read his own notes. Such ideas are scandalous. I wanted a chronology built upon the idea of Watson's words as facts. Since I could not find one, I created one."

Let me say now that I think that anyone who attempts to do a full chronology of the cases is to be applauded. It is a daunting undertaking. One not to take lightly. I'm not sure, however, about it being a rite of passage. But, I'm not here to bury Caeser...just his work. Let's start, shall we?

Whenever I get a new chronology (and I'm past the 25-of-them mark) I turn to two cases in particular because of their rather blunt assertions about dates (from Watson) that are completely wrong. One is 'The Solitary Cyclist' (SOLI). In this story The Good Doctor tells us "On referring to my note-book for the year 1895, I find that it was upon Saturday, April 23rd, that we first heard of Miss Violet Smith." As anyone knows who has followed me or any other chronologist, April 23rd, 1895, was a Tuesday. As such, I was anxious to see how Mr. Miller solved this problem.

He tells us that he is "forced by my narrative to turn hypocrite." He accepts the fact that the story's events did take place on a Saturday, and that...now follow me here..."In his haste to put the stories together for The Strand's deadlines, [Watson] erred when reading his notes and compounded two dates." To his credit, though, he says in an earlier paragraph that "I must accuse Watson of misreading his own notes. Just this once. Only once." Well, I'm glad we got that settled.

The other story I look at it is 'The Man with the Twisted Lip' (TWIS). In it Watson tells us that it was Friday, June 19th, 1889. June 19th, 1889, was a Wednesday. Mr. Miller looks at the case and reminds us of this exchange between Watson and Isa Whitney:

"I say, Watson, what o'clock is it?"

"Nearly eleven."

"Of what day?"

"Of Friday, June 19th."

"Good heavens! I thought it was Wednesday. It is Wednesday. What d'you want to frighten a chap for?"

He goes on to justify this by saying that Watson was just trying to scare Isa by making the date wrong, and that Watson told "a rare white lie" and that he is "no natural liar." I was already not impressed.

But, in order to give it somewhat of a chance, I read it straight through. It's quite an easy read, but I found myself shaking my head an awful lot. I'll give you one more example of his type of logic, and then I'll give you my final thoughts.

'Wisteria Lodge' (WIST). This case gives most chronologists fits because Watson tells us it happened in March 1892. Anyone who is even the tiniest bit interested in Sherlockian chronology knows that from 1891 to 1894 Holmes was on his Great Hiatus. The world, including Watson, believed him dead at the bottom of Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland. How is this possible? Mr. Miller tells us that it did in fact happen when Watson says it did, and this is how:

"I'll wager Holmes and Mycroft used a hypnotist. Watson was hypnotised just before Holmes's return to make him think that living at 221b with Holmes was still the norm. He woke in his old room and the charade began. When it was times for Holmes to leave him again, Watson was hypnotised to forget the entire return."

Mr. Miller thinks that Holmes came back to work on a case, and then finds all kinds of "evidence" in the story to prove that he is right. It's doable, I think, since he wasn't dead, but the whole hypnotising thing? Sorry. It doesn't compute for me.

I will not say I'm not impressed by a few things. He does have dates that seem plausible, and he does go along with a number of others on some of the more acceptable timelines. But, Mr. Miller misses out on something huge. Something I've talked about before. It breaks down for me like this:

If you're going to write a chronology, you must look at every little detail in the stories. Mr. Miller does that (partially) but only when he needs further "proof" to back up his unusual dates for a case. Otherwise all he does is compare the stories on a thin level of weather reports and comparing dates with each other. He doesn't bother with any other details in the stories. He doesn't look at vernacular, or construction, or any other facet of Victorian London in order to find a correct date. This is an example of lazy chronology building, I'm afraid. If he wants his "rite of passage" and he believes this book gives him that, then more power to him. But, I will not look at this as a serious effort.

I said in my interview on I Hear of Sherlock Everywhere (at the 17:35 mark) that a thin chronology book is a problem. Mr. Miller's book is fairly thin. I was vexed by that when it arrived at my doorstep.

As a juxtaposition, in Mr. Miller's interview on that podcast (at the 40:30 mark and on for the next two minutes), he tells us that he has noticed something strange about these lines from 'A Case of Identity' (IDEN):

"The man sat huddled up in his chair, with his head sunk upon his breast, like one who is utterly crushed. Holmes stuck his feet up on the corner of the mantelpiece, and leaning back with his hands in his pockets, began talking, rather to himself, as it seemed, than to us."

According to him, this means that Holmes had two prosthetic feet. Yep. Fake feet. Ones he removed and sat up on the mantelpiece. It reminded me of an illustration I saw in PUNCH magazine years ago, and kept because it looked so comfortable and funny. (Though Mr. Miller thinks the position impossible.)

I'll end my torture here and say that the hardest part to swallow about this chronology is the debate about Watson's wives. Yes, this is a major stumbling block for anyone wanting to find a proper timeline for these cases, but Mr. Miller decides to not let the dates fight each other, and accepts each as an accurate item. As such, he finds that Watson was married six times. Yep...six. I should've stopped when I found out that little tidbit, but I'm a sucker for this part of the hobby. Even when a book comes out that will serve no purpose other than to lessen the efforts of others.

Here's the link for my interview:

https://soundcloud.com/ihearofsherlock/episode-144-the-chronologies

Here's the link for his interview:

https://soundcloud.com/ihearofsherlock/watson-does-not-lie-doyles

I will also add this review by a friend of mine:

http://othersperhapslessexcusable.com/a-dim-vague-perception-of-the-truth-stud/?fbclid=IwAR2bZCmIhbL2QSYM3GS4X4T4pawg0VPxKgr1du0-Lp00zQpd6B0cCBrfqTg

I will happily put all of Mr. Miller's dates in my databases, and I will refer to them when the times comes. It doesn't matter if I agree with them or not, it's all about the debates and variations. His info will be a welcome edition, and I hope he does more with it as this is one of the few times people like me get to have our part of the community spotlighted...even if just for a moment.

I'll see you next month. I appreciate you stopping in, and as always...thanks for reading.

Paul Thomas Miller is a Holmesian from the U.K. I'm afraid I don't know a lot about him, but I do know he's an active member in our hobby. Recently he put out a book called Watson Does Not Lie, which is a chronology based on the idea that...well, here's what he says on the back of the book:

"I was told the creation of a Holmesian Chronology is practically a rite of passage. I was told once you have managed to make sense of the sixty stories you emerge a rookie no more. I was told it is a task that improves you and your understanding of The Canon.

I'm not so sure...

Too many chronologists resorted to claiming either Watson lied, or could not read his own notes. Such ideas are scandalous. I wanted a chronology built upon the idea of Watson's words as facts. Since I could not find one, I created one."

Let me say now that I think that anyone who attempts to do a full chronology of the cases is to be applauded. It is a daunting undertaking. One not to take lightly. I'm not sure, however, about it being a rite of passage. But, I'm not here to bury Caeser...just his work. Let's start, shall we?

Whenever I get a new chronology (and I'm past the 25-of-them mark) I turn to two cases in particular because of their rather blunt assertions about dates (from Watson) that are completely wrong. One is 'The Solitary Cyclist' (SOLI). In this story The Good Doctor tells us "On referring to my note-book for the year 1895, I find that it was upon Saturday, April 23rd, that we first heard of Miss Violet Smith." As anyone knows who has followed me or any other chronologist, April 23rd, 1895, was a Tuesday. As such, I was anxious to see how Mr. Miller solved this problem.

He tells us that he is "forced by my narrative to turn hypocrite." He accepts the fact that the story's events did take place on a Saturday, and that...now follow me here..."In his haste to put the stories together for The Strand's deadlines, [Watson] erred when reading his notes and compounded two dates." To his credit, though, he says in an earlier paragraph that "I must accuse Watson of misreading his own notes. Just this once. Only once." Well, I'm glad we got that settled.

The other story I look at it is 'The Man with the Twisted Lip' (TWIS). In it Watson tells us that it was Friday, June 19th, 1889. June 19th, 1889, was a Wednesday. Mr. Miller looks at the case and reminds us of this exchange between Watson and Isa Whitney:

"I say, Watson, what o'clock is it?"

"Nearly eleven."

"Of what day?"

"Of Friday, June 19th."

"Good heavens! I thought it was Wednesday. It is Wednesday. What d'you want to frighten a chap for?"

He goes on to justify this by saying that Watson was just trying to scare Isa by making the date wrong, and that Watson told "a rare white lie" and that he is "no natural liar." I was already not impressed.

But, in order to give it somewhat of a chance, I read it straight through. It's quite an easy read, but I found myself shaking my head an awful lot. I'll give you one more example of his type of logic, and then I'll give you my final thoughts.

'Wisteria Lodge' (WIST). This case gives most chronologists fits because Watson tells us it happened in March 1892. Anyone who is even the tiniest bit interested in Sherlockian chronology knows that from 1891 to 1894 Holmes was on his Great Hiatus. The world, including Watson, believed him dead at the bottom of Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland. How is this possible? Mr. Miller tells us that it did in fact happen when Watson says it did, and this is how:

"I'll wager Holmes and Mycroft used a hypnotist. Watson was hypnotised just before Holmes's return to make him think that living at 221b with Holmes was still the norm. He woke in his old room and the charade began. When it was times for Holmes to leave him again, Watson was hypnotised to forget the entire return."

Mr. Miller thinks that Holmes came back to work on a case, and then finds all kinds of "evidence" in the story to prove that he is right. It's doable, I think, since he wasn't dead, but the whole hypnotising thing? Sorry. It doesn't compute for me.

I will not say I'm not impressed by a few things. He does have dates that seem plausible, and he does go along with a number of others on some of the more acceptable timelines. But, Mr. Miller misses out on something huge. Something I've talked about before. It breaks down for me like this:

If you're going to write a chronology, you must look at every little detail in the stories. Mr. Miller does that (partially) but only when he needs further "proof" to back up his unusual dates for a case. Otherwise all he does is compare the stories on a thin level of weather reports and comparing dates with each other. He doesn't bother with any other details in the stories. He doesn't look at vernacular, or construction, or any other facet of Victorian London in order to find a correct date. This is an example of lazy chronology building, I'm afraid. If he wants his "rite of passage" and he believes this book gives him that, then more power to him. But, I will not look at this as a serious effort.

I said in my interview on I Hear of Sherlock Everywhere (at the 17:35 mark) that a thin chronology book is a problem. Mr. Miller's book is fairly thin. I was vexed by that when it arrived at my doorstep.

As a juxtaposition, in Mr. Miller's interview on that podcast (at the 40:30 mark and on for the next two minutes), he tells us that he has noticed something strange about these lines from 'A Case of Identity' (IDEN):

"The man sat huddled up in his chair, with his head sunk upon his breast, like one who is utterly crushed. Holmes stuck his feet up on the corner of the mantelpiece, and leaning back with his hands in his pockets, began talking, rather to himself, as it seemed, than to us."

According to him, this means that Holmes had two prosthetic feet. Yep. Fake feet. Ones he removed and sat up on the mantelpiece. It reminded me of an illustration I saw in PUNCH magazine years ago, and kept because it looked so comfortable and funny. (Though Mr. Miller thinks the position impossible.)

I'll end my torture here and say that the hardest part to swallow about this chronology is the debate about Watson's wives. Yes, this is a major stumbling block for anyone wanting to find a proper timeline for these cases, but Mr. Miller decides to not let the dates fight each other, and accepts each as an accurate item. As such, he finds that Watson was married six times. Yep...six. I should've stopped when I found out that little tidbit, but I'm a sucker for this part of the hobby. Even when a book comes out that will serve no purpose other than to lessen the efforts of others.

Here's the link for my interview:

https://soundcloud.com/ihearofsherlock/episode-144-the-chronologies

Here's the link for his interview:

https://soundcloud.com/ihearofsherlock/watson-does-not-lie-doyles

I will also add this review by a friend of mine:

http://othersperhapslessexcusable.com/a-dim-vague-perception-of-the-truth-stud/?fbclid=IwAR2bZCmIhbL2QSYM3GS4X4T4pawg0VPxKgr1du0-Lp00zQpd6B0cCBrfqTg

I will happily put all of Mr. Miller's dates in my databases, and I will refer to them when the times comes. It doesn't matter if I agree with them or not, it's all about the debates and variations. His info will be a welcome edition, and I hope he does more with it as this is one of the few times people like me get to have our part of the community spotlighted...even if just for a moment.

I'll see you next month. I appreciate you stopping in, and as always...thanks for reading.

Monday, November 18, 2019

The Good Doctor Is In

There was a small incident on the Historical Sherlock Facebook Page on the first day of this month. Nothing controversial, just something not often found on the site - a heckler. Well, maybe not a heckler, but someone who decided what I did there was silly or pointless. I'd like to talk about it if I may.

I had made a Post about something I found in 'The Six Napoleons' (SIXN). It was really no different than many of the hundreds of others I've done, and stood out in no particular way. As usual, I looked for something from The Canon, dove into, and came up with an interesting tidbit. I tied Holmes and/or Watson into it, and shared it with the world. It's the standard, and one I hope isn't becoming stale. (If it does, please tell me.)

The post was about Pitt Street in Kingston. A short little street with absolutely nothing exceptional about it. However, I found a way to give it some life. Then I got this Comment...

I was a little taken aback as I thought everyone understood the premise of the Page. I pondered an answer, and then wrote this response...

I've blacked out the person's name so as to protect them (to a point, I guess), but the Comment and response is still there if you want to see them in raw form. Other folks got in on it calling what she was saying heresy. We're pretty serious about The Game, but we don't need or want someone calling us out on it.

I became a Sherlockian in 1997. Officially. I had been a Holmes fan from before that, but joined The Illustrious Clients of Indianapolis and have been with them ever since. I've enjoyed a generous speaking tour for the last decade, have been published in many different books, journals, and newsletters, and have assisted with chronological research on others. The chronology aspect of the hobby continues to be the part that holds my attention, and I'm pretty sure it always will. There's still so much to do with all of the information I have, and all of it that I don't yet have. It will keep me busy until death.

Playing The Game, or The Grand Game, has been around for the better part of a century, and we play it knowing that it's all tongue-in-cheek. Some play it with a seriousness I can appreciate, but will not attain, while for others it's something to do every once in a while. I fall more toward the serious side, but it's because of the research. I LOVE research. I also love Victorian London. I love Sherlock Holmes and The Canon and Watson and Lestrade and Adler and...you get the idea. It all comes together for me in a way that is unique in the hobby (the way I approach it, anyway.)

Basically, it comes down to this...

We in this hobby know Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John H. Watson are not real, and that the entire Canon is a work of fiction. It's true that some people around the planet don't know that, but it's a rare occasion anymore. We find ourselves in love with the stories and the characters for different reasons. Some love the social aspect of it all, some the partnership between The Amazing Two, some the Victorian era part, and some the historical part of it.

When an author writes anything set in an actual time period from our planet in our history it's bound to contain some things that are true. I've written several pastiches and did research on streets and hansom cab numbers and police officer uniforms, and all just to make sure I had them right. Arthur Conan Doyle (later Sir) had the advantage of being right in the middle of the time period he was writing about. His insights were invaluable. My personal enjoyment of the Holmes stories are the details in those stories. I am perfectly happy tracking down info about any little thing contained in them, and have plenty to research for as long as I possibly can.

The great thing is that so many other people have done the same thing for a long time. We rip these cases apart and put it all under our own magnifying glass. But, it's all done for fun. Some make money from Holmes and Watson, but that's not what I'm in it for. Research makes me happy, and if I get to do it on some of the greatest stories ever told featuring the greatest detective of all time who lived at the most famous address in the history of literature, well, I'd call all of those huge bonuses.

I love what I do, and so do a lot of other people who do similar work. No therapy need apply.

Thank you for getting this far. I wouldn't call this a rant, but more of a defense against those who (for some reason) think people like me are so deluded we forget about reality. Well, I can't speak for others, but I don't. This is a work of love for me, and even if I didn't have a single reader, I'd still do it.

I'll see you in about a week for the next post, and I promise it will be about chronology. I'll see you then, and as always...thanks for reading.

I had made a Post about something I found in 'The Six Napoleons' (SIXN). It was really no different than many of the hundreds of others I've done, and stood out in no particular way. As usual, I looked for something from The Canon, dove into, and came up with an interesting tidbit. I tied Holmes and/or Watson into it, and shared it with the world. It's the standard, and one I hope isn't becoming stale. (If it does, please tell me.)

The post was about Pitt Street in Kingston. A short little street with absolutely nothing exceptional about it. However, I found a way to give it some life. Then I got this Comment...

I was a little taken aback as I thought everyone understood the premise of the Page. I pondered an answer, and then wrote this response...

I've blacked out the person's name so as to protect them (to a point, I guess), but the Comment and response is still there if you want to see them in raw form. Other folks got in on it calling what she was saying heresy. We're pretty serious about The Game, but we don't need or want someone calling us out on it.

I became a Sherlockian in 1997. Officially. I had been a Holmes fan from before that, but joined The Illustrious Clients of Indianapolis and have been with them ever since. I've enjoyed a generous speaking tour for the last decade, have been published in many different books, journals, and newsletters, and have assisted with chronological research on others. The chronology aspect of the hobby continues to be the part that holds my attention, and I'm pretty sure it always will. There's still so much to do with all of the information I have, and all of it that I don't yet have. It will keep me busy until death.

Playing The Game, or The Grand Game, has been around for the better part of a century, and we play it knowing that it's all tongue-in-cheek. Some play it with a seriousness I can appreciate, but will not attain, while for others it's something to do every once in a while. I fall more toward the serious side, but it's because of the research. I LOVE research. I also love Victorian London. I love Sherlock Holmes and The Canon and Watson and Lestrade and Adler and...you get the idea. It all comes together for me in a way that is unique in the hobby (the way I approach it, anyway.)

Basically, it comes down to this...

We in this hobby know Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John H. Watson are not real, and that the entire Canon is a work of fiction. It's true that some people around the planet don't know that, but it's a rare occasion anymore. We find ourselves in love with the stories and the characters for different reasons. Some love the social aspect of it all, some the partnership between The Amazing Two, some the Victorian era part, and some the historical part of it.

When an author writes anything set in an actual time period from our planet in our history it's bound to contain some things that are true. I've written several pastiches and did research on streets and hansom cab numbers and police officer uniforms, and all just to make sure I had them right. Arthur Conan Doyle (later Sir) had the advantage of being right in the middle of the time period he was writing about. His insights were invaluable. My personal enjoyment of the Holmes stories are the details in those stories. I am perfectly happy tracking down info about any little thing contained in them, and have plenty to research for as long as I possibly can.

The great thing is that so many other people have done the same thing for a long time. We rip these cases apart and put it all under our own magnifying glass. But, it's all done for fun. Some make money from Holmes and Watson, but that's not what I'm in it for. Research makes me happy, and if I get to do it on some of the greatest stories ever told featuring the greatest detective of all time who lived at the most famous address in the history of literature, well, I'd call all of those huge bonuses.

I love what I do, and so do a lot of other people who do similar work. No therapy need apply.

Thank you for getting this far. I wouldn't call this a rant, but more of a defense against those who (for some reason) think people like me are so deluded we forget about reality. Well, I can't speak for others, but I don't. This is a work of love for me, and even if I didn't have a single reader, I'd still do it.

I'll see you in about a week for the next post, and I promise it will be about chronology. I'll see you then, and as always...thanks for reading.

Wednesday, October 23, 2019

A Chronological Crossover (Part 2)

Now for the second half of this wonderful paper. I love the fact that it was split perfectly in half when originally published. It's almost like it was created just to be a two-part blog post one day. I know it's a bit lengthy, and in today's hurry-up world it may be unsavory to read something so long especially when you might have only a slight interest, but I only put it on here because it seemed a perfect example of what someone like me does to satisfy that chronological itch.

I do have some qualms with the paper, though, but I'll let you continue reading before I bore you with them. So, back to it you go. Enjoy.

Well, there it all is. It's pretty convincing, but there are a couple of points I'd like to look at. (Oh, and did you like the collar advertisement at the end? I threw that in because it was actually there, and it's fun.)

First, I have always been intrigued by the Sickert part of the Ripper story. I don't believe he was the killer, but he had to have had some hand it in it somehow. There are just too many places where he pops up to not have been involved in some way. For the record, I believe the actual killer was named in this book:

I won't give it away, but if you're interested in the Ripper case at all, then I suggest getting this (rather long) masterpiece. You won't be disappointed.

The other point that bugs me about this paper is that it ignores every other chronologist (and Watson - which is okay sometimes) when it comes to the time of year. Yes, the argument is good for it being later on the calendar, but that means all other evidence has to be ignored. The case is clearly in the spring, and this is what I've talked about before - examining everything about a story to find it's date. In this case, Bill doesn't do that: he only accepts a different date based on the research he's done, and does not try and correlate that absolute correct time of year to fit into his logic. I still like the paper, and will happily refer to it in future conversations, but only as a side note...not a definitive answer to the dating of this story.

I love what he's done, but more work would have to be done with the known facts of the details of the case before I would say this is an acceptable alternate date.

PHEW! Well, this has been a long one. I hope it was worth it, and that you enjoyed it. The great thing about all of this is that you don't have to hurry through it - come back to it another time. Look at all of it again someday. It's all about leisure and enjoyment. That's what I try and deliver, and I can only hope that's what you get out of all of this. I'll see you on Facebook, and right back here next month. I truly appreciate your time, and as always...thanks for reading.

p.s. At the request of one of you loyal readers, I am adding the footnotes page. I thought there were several, but there's just the one. (The other pages were something else.) Anyhoo, here you go.

I do have some qualms with the paper, though, but I'll let you continue reading before I bore you with them. So, back to it you go. Enjoy.

Well, there it all is. It's pretty convincing, but there are a couple of points I'd like to look at. (Oh, and did you like the collar advertisement at the end? I threw that in because it was actually there, and it's fun.)

First, I have always been intrigued by the Sickert part of the Ripper story. I don't believe he was the killer, but he had to have had some hand it in it somehow. There are just too many places where he pops up to not have been involved in some way. For the record, I believe the actual killer was named in this book:

I won't give it away, but if you're interested in the Ripper case at all, then I suggest getting this (rather long) masterpiece. You won't be disappointed.

The other point that bugs me about this paper is that it ignores every other chronologist (and Watson - which is okay sometimes) when it comes to the time of year. Yes, the argument is good for it being later on the calendar, but that means all other evidence has to be ignored. The case is clearly in the spring, and this is what I've talked about before - examining everything about a story to find it's date. In this case, Bill doesn't do that: he only accepts a different date based on the research he's done, and does not try and correlate that absolute correct time of year to fit into his logic. I still like the paper, and will happily refer to it in future conversations, but only as a side note...not a definitive answer to the dating of this story.

I love what he's done, but more work would have to be done with the known facts of the details of the case before I would say this is an acceptable alternate date.

PHEW! Well, this has been a long one. I hope it was worth it, and that you enjoyed it. The great thing about all of this is that you don't have to hurry through it - come back to it another time. Look at all of it again someday. It's all about leisure and enjoyment. That's what I try and deliver, and I can only hope that's what you get out of all of this. I'll see you on Facebook, and right back here next month. I truly appreciate your time, and as always...thanks for reading.

p.s. At the request of one of you loyal readers, I am adding the footnotes page. I thought there were several, but there's just the one. (The other pages were something else.) Anyhoo, here you go.

Tuesday, October 22, 2019

A Chronological Crossover (Part 1)

I love historical mysteries. Subjects like the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, the controversial death of Ambrose Bierce, The Shakespeare Authorship Question, what ultimately happened to Thomas P. 'Boston' Corbett (the man who shot John Wilkes Booth), and the 1888 London murders of Jack the Ripper are my kind of reading. Now, Sherlock Holmes has been tied to Mr. The Ripper many, many, many times, and it can get tiresome, but every once in a while something falls into my lap which begs me to read it. That's what we're going to discuss today.

We are right in the middle of what you might call "Ripper season." The five "canonical" murders all occurred in 1888, with four in September and one in November. And given that Hallowe'en is creeping up on us, this seemed fitting. I am not trying to glorify the murders, nor take away from the victims, but merely show you a glimpse into a couple of my worlds - ones that are crossing over into each other. Let's get to the good stuff, shall we?

Back in 1986 a Sherlockian named William 'Bill' Cochran published an article in one of his society's publications. Bill runs The Occupants of the Empty House in Du Quoin, Illinois. (That's really close to where I'm originally from.) I contacted him and asked if I could use said article on my blog, and he graciously granted me permission. As such, I am going to simply put the entire piece on here for you to peruse. I have scanned all the pages (with my little hand-held scanner)(which will explain some of the small irregularities) and will just paste them here. Transcribing it would take too long, and I'm lousy at condensing things.

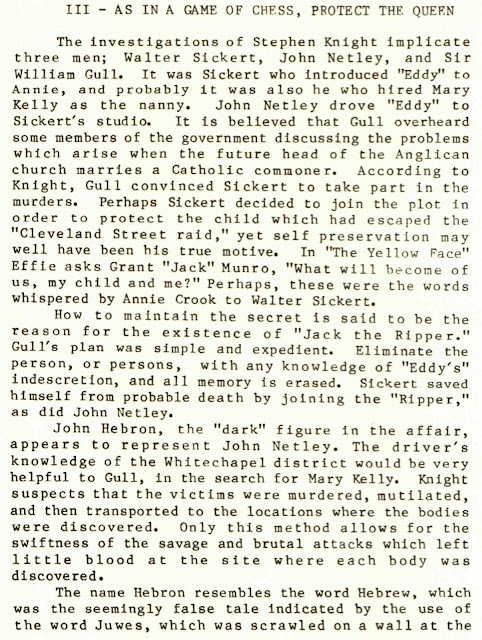

I'm going to do the first five pages now, and the other five in a couple of days. The amount of research that went into this is staggering, and it shows how deep a chronologist sometimes has to go in order to secure a possible date for a case. Bill is not a chronologist, but after reading this he is definitely an honorary one. Enjoy.

Intriguing, eh? And it gets better. We haven't even gotten to the chronology part yet. Again, I believe this is a great paper, and it really gives a sense of the "pains" people like me go through just to put a date to just one case. And there are 58 more! (I don't count 'The Mazarin Stone' [MAZA]. I'm working on a theory that it was merely a play written by Watson and not an actual case.)

I'll see you in a couple of days with the rest of the article, so be good until then, and remember that The Great Pumpkin is watching you. See you then, and as always...thanks for reading.

We are right in the middle of what you might call "Ripper season." The five "canonical" murders all occurred in 1888, with four in September and one in November. And given that Hallowe'en is creeping up on us, this seemed fitting. I am not trying to glorify the murders, nor take away from the victims, but merely show you a glimpse into a couple of my worlds - ones that are crossing over into each other. Let's get to the good stuff, shall we?

Back in 1986 a Sherlockian named William 'Bill' Cochran published an article in one of his society's publications. Bill runs The Occupants of the Empty House in Du Quoin, Illinois. (That's really close to where I'm originally from.) I contacted him and asked if I could use said article on my blog, and he graciously granted me permission. As such, I am going to simply put the entire piece on here for you to peruse. I have scanned all the pages (with my little hand-held scanner)(which will explain some of the small irregularities) and will just paste them here. Transcribing it would take too long, and I'm lousy at condensing things.

I'm going to do the first five pages now, and the other five in a couple of days. The amount of research that went into this is staggering, and it shows how deep a chronologist sometimes has to go in order to secure a possible date for a case. Bill is not a chronologist, but after reading this he is definitely an honorary one. Enjoy.

Intriguing, eh? And it gets better. We haven't even gotten to the chronology part yet. Again, I believe this is a great paper, and it really gives a sense of the "pains" people like me go through just to put a date to just one case. And there are 58 more! (I don't count 'The Mazarin Stone' [MAZA]. I'm working on a theory that it was merely a play written by Watson and not an actual case.)

I'll see you in a couple of days with the rest of the article, so be good until then, and remember that The Great Pumpkin is watching you. See you then, and as always...thanks for reading.

Friday, September 27, 2019

No Ordnary Ordnance...Part 2

I don't do a lot of two-parters, but this one would definitely have been too long for a single, so I split it up. (Also, I still needed two posts for the month on here, so it works out in more ways than one.) So, let's continue taking a look at my favorite Victorian map of London.

You'll recall the sea level numbers that are every few yards or so on the map? They sometimes were listed with the letters B.M with them. That stands for Bench Mark (or Benchmark), and I'll let Wikipedia give you an explanation:

"The term benchmark, or bench mark, originates from the chiseled horizontal marks that surveyors made in stone structures, into which an angle-iron could be placed to form a "bench" for a leveling rod, thus ensuring that a leveling rod could be accurately repositioned in the same place in the future. These marks were usually indicated with a chiseled arrow below the horizontal line."

You'll see the symbol on the map just above and to the left of the B.M. and number. It kind of looks like an arrow. Now, I talked about these on Facebook a little over a year ago back on August 29, 2018, and their appearance in The Canon. Here's the original post:

"In 'The Gloria Scott' (GLOR) we meet a truly charming man named Jack Prendergast. Okay, not really. But we do get to see him in his prison uniform - the one covered in arrows. Well, those are actually called 'broad arrows' and were a creation of Henry VIII. It was a symbol used to signify that something belonged to the Crown.

Used as a mark of shame and a hindrance in escaping, the arrows were used until 1922. What we can't see in the illustration is that nails were often driven into a prisoner's boot soles in an arrow configuration, as well. Basically, they would point the way if a prisoner escaped. Clever, eh?"

Let's look at another section of the map with different things to examine.

This one features a very prominent B.P. That stands for Boundary Post (or Pole). This abbreviation has a counterpart in B.S. - Boundary Stone. (Not shown here.) These were both used to demarcate property or business edges. Now, on a more unpleasant note, I'm not sure why these maps didn't use just a simple 'U' for the urinals, but they didn't. Above the urinal, though, is F.W. That's for Face of Wall. Toward the bottom of this section is P.O. This is a common set of initials for a lot of people, and are for Post Office.

Other initials that you can find in different areas are S.P. This one can stand for Sewer Pipe or Signal Post. R.S. - Rain Spout. V.P. - Vent Pipe. D.B. - Dust Bin. H.W. - Hedge Row. D.P. - Dung Pit. It just goes on and on. You'll see churches, cemeteries, cabmen's shelters, depots, schools, troughs, gardens, docks...there's just so much.

Now, I could write many more of these posts about the different things found on these old ordnance maps, but I won't. Instead, I want you to look for yourself. I want you to spend some time studying this one and others like it just to see what you can discover. These things are so vast and detailed that there's always something new to find. So, please do so. After all, it's all about keeping Sherlock Holmes on the minds and lips of the next generations, right?

In the interest of fairness, I'll give you the link instead of making you look for it. The great thing is that the site has not just the one map, but a lot of others. Plenty to choose from. And you can do overlays, and side-by-side views. It's extraordinary, and will keep you busy for a long time.

Here you go...

https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17&lat=51.5085&lon=-0.0235&layers=163&b=1

It's been fun bringing this to you, and I hope it helps you understand part of what I do here and where I get some of my information. Please take it and run with it. I encourage it and wait patiently. I'll see you next time, and as always...thanks for reading.

You'll recall the sea level numbers that are every few yards or so on the map? They sometimes were listed with the letters B.M with them. That stands for Bench Mark (or Benchmark), and I'll let Wikipedia give you an explanation:

"The term benchmark, or bench mark, originates from the chiseled horizontal marks that surveyors made in stone structures, into which an angle-iron could be placed to form a "bench" for a leveling rod, thus ensuring that a leveling rod could be accurately repositioned in the same place in the future. These marks were usually indicated with a chiseled arrow below the horizontal line."

You'll see the symbol on the map just above and to the left of the B.M. and number. It kind of looks like an arrow. Now, I talked about these on Facebook a little over a year ago back on August 29, 2018, and their appearance in The Canon. Here's the original post:

"In 'The Gloria Scott' (GLOR) we meet a truly charming man named Jack Prendergast. Okay, not really. But we do get to see him in his prison uniform - the one covered in arrows. Well, those are actually called 'broad arrows' and were a creation of Henry VIII. It was a symbol used to signify that something belonged to the Crown.

Used as a mark of shame and a hindrance in escaping, the arrows were used until 1922. What we can't see in the illustration is that nails were often driven into a prisoner's boot soles in an arrow configuration, as well. Basically, they would point the way if a prisoner escaped. Clever, eh?"

Let's look at another section of the map with different things to examine.

This one features a very prominent B.P. That stands for Boundary Post (or Pole). This abbreviation has a counterpart in B.S. - Boundary Stone. (Not shown here.) These were both used to demarcate property or business edges. Now, on a more unpleasant note, I'm not sure why these maps didn't use just a simple 'U' for the urinals, but they didn't. Above the urinal, though, is F.W. That's for Face of Wall. Toward the bottom of this section is P.O. This is a common set of initials for a lot of people, and are for Post Office.

Other initials that you can find in different areas are S.P. This one can stand for Sewer Pipe or Signal Post. R.S. - Rain Spout. V.P. - Vent Pipe. D.B. - Dust Bin. H.W. - Hedge Row. D.P. - Dung Pit. It just goes on and on. You'll see churches, cemeteries, cabmen's shelters, depots, schools, troughs, gardens, docks...there's just so much.

Now, I could write many more of these posts about the different things found on these old ordnance maps, but I won't. Instead, I want you to look for yourself. I want you to spend some time studying this one and others like it just to see what you can discover. These things are so vast and detailed that there's always something new to find. So, please do so. After all, it's all about keeping Sherlock Holmes on the minds and lips of the next generations, right?

In the interest of fairness, I'll give you the link instead of making you look for it. The great thing is that the site has not just the one map, but a lot of others. Plenty to choose from. And you can do overlays, and side-by-side views. It's extraordinary, and will keep you busy for a long time.

Here you go...

https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=17&lat=51.5085&lon=-0.0235&layers=163&b=1

It's been fun bringing this to you, and I hope it helps you understand part of what I do here and where I get some of my information. Please take it and run with it. I encourage it and wait patiently. I'll see you next time, and as always...thanks for reading.

Wednesday, September 25, 2019

No Ordnary Ordnance...Part 1

I love going through photographs of London from the time of Holmes and Watson. I go through thousands of them knowing full-well I may only find a few I can research and use. It's still worth it, though, because I continue to learn about their time and the things they experienced. Whenever I find something I do my best to nail down its exact location on a map. But not just any map - one from 1895. (By the way...this one's going to be a two-parter.)

I came across this ordnance map some years ago on a Facebook post. I had heard inklings of it in the Sherlockian world, but hadn't seen it for myself. Once I had, it never left the opened tabs across the top of my laptop. Honest! I have it there all the time. (And it's always right next to the Search the Canon tab.)

I spent some time familiarising myself with all of the different symbols and initials, and found that some of them took more time than others. (I realize this may not be new information to some of you, but there are others who may not know. This is for them.) Let's take a look at a section of Baker Street that has some examples.

This one area has several things in it we can explore. First is the ventilators. These are pretty self-explanatory, and deal with the Underground running right under the area. You'll notice the letters B.O. Ordnance map sites that list what abbreviations are don't have this one. It took a bit more looking, and we'll get to what I found it in a minute.

The letters F.P. stand for Fire Plug. These were spots in the road or street where a plug in the water main below could be accessed by the fire department. There are thousands of these all over this map. They're not the same as fire hydrants, but they were the first (sort-of) version of them. Also in the picture is P.L.B. This is for Pillar Letter Box. You know the ones I mean...

See the letters C.R. on the map? That is for Center of Road. Off to the left side of the shot (that you can't see) is the phrase Div. of Parly. Boro. Bdy. (Division of Parliamentary Borough Boundary) and the C.R. notated exactly where that boundary was. These don't always run right down the middle of a street, however, and like any other boundary line it can go almost anywhere. P.H. is for Public House. England was pretty proud of these as they appear everywhere, and sometimes multiple ones existed within just yards of each other. They weren't always the nicest of places, but they still made it on the maps.

Now let's look at B.O. I have yet to find an ordnance map legend that has these initials on it. I had a suspicion it was for either Booking Office or Boarding Office. A bit more research led me to my answer:

This paragraph is from an article called 'Booking Offices at Baker Street' by a Brian Pask from 2019. (Sorry about the size.) It talks about the very ones in the section from above and thus ends the mystery of the B.O.

Here's another section that has a few others...

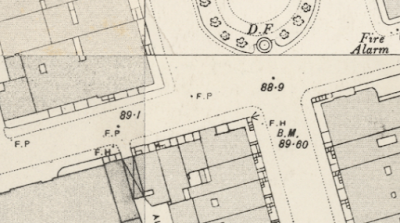

Sticking with the fire thing we find F.H. here. That's for Fire Hose. In a few places I saw just the letter H. According to the abbreviation lists it stands for a hydrant, and that makes sense to me. On the right you see the words Fire Alarm. There are more examples on the map, this is just one I found that doesn't use the initials F.A. for that. The letters D.F. at the top of the shot is for Drinking Fountain, and since it's in a park it might've been a bit more obvious than others. (I like to be thorough, though.)

The numbers that you see on both sections of map here are heights above sea level for mainland Great Britain. You'll notice that sometimes they accompany the letters B.M. That's where we'll pick it up next time.

Side note:

I get emails quite a bit from people who want to know what site I use for this or that, and where I get my information, and so on and so forth. I answer all of them, but I thought I would answer a couple of them with this post by saying that this is my go-to map. I will spend time just studying it, and it's still surprising to me what nuggets I can mine out of it.

Again, I know this won't be new to some of you, but I like being very open with what I do, and if someone out there can use this and continue (or add to) the research, then I'm all for it.

Anyway, the other half of this will be in the next day or so. I'll see you then, and as always...thanks for reading.

I came across this ordnance map some years ago on a Facebook post. I had heard inklings of it in the Sherlockian world, but hadn't seen it for myself. Once I had, it never left the opened tabs across the top of my laptop. Honest! I have it there all the time. (And it's always right next to the Search the Canon tab.)

I spent some time familiarising myself with all of the different symbols and initials, and found that some of them took more time than others. (I realize this may not be new information to some of you, but there are others who may not know. This is for them.) Let's take a look at a section of Baker Street that has some examples.

This one area has several things in it we can explore. First is the ventilators. These are pretty self-explanatory, and deal with the Underground running right under the area. You'll notice the letters B.O. Ordnance map sites that list what abbreviations are don't have this one. It took a bit more looking, and we'll get to what I found it in a minute.

The letters F.P. stand for Fire Plug. These were spots in the road or street where a plug in the water main below could be accessed by the fire department. There are thousands of these all over this map. They're not the same as fire hydrants, but they were the first (sort-of) version of them. Also in the picture is P.L.B. This is for Pillar Letter Box. You know the ones I mean...

See the letters C.R. on the map? That is for Center of Road. Off to the left side of the shot (that you can't see) is the phrase Div. of Parly. Boro. Bdy. (Division of Parliamentary Borough Boundary) and the C.R. notated exactly where that boundary was. These don't always run right down the middle of a street, however, and like any other boundary line it can go almost anywhere. P.H. is for Public House. England was pretty proud of these as they appear everywhere, and sometimes multiple ones existed within just yards of each other. They weren't always the nicest of places, but they still made it on the maps.

Now let's look at B.O. I have yet to find an ordnance map legend that has these initials on it. I had a suspicion it was for either Booking Office or Boarding Office. A bit more research led me to my answer:

This paragraph is from an article called 'Booking Offices at Baker Street' by a Brian Pask from 2019. (Sorry about the size.) It talks about the very ones in the section from above and thus ends the mystery of the B.O.

Here's another section that has a few others...

Sticking with the fire thing we find F.H. here. That's for Fire Hose. In a few places I saw just the letter H. According to the abbreviation lists it stands for a hydrant, and that makes sense to me. On the right you see the words Fire Alarm. There are more examples on the map, this is just one I found that doesn't use the initials F.A. for that. The letters D.F. at the top of the shot is for Drinking Fountain, and since it's in a park it might've been a bit more obvious than others. (I like to be thorough, though.)

The numbers that you see on both sections of map here are heights above sea level for mainland Great Britain. You'll notice that sometimes they accompany the letters B.M. That's where we'll pick it up next time.

Side note:

I get emails quite a bit from people who want to know what site I use for this or that, and where I get my information, and so on and so forth. I answer all of them, but I thought I would answer a couple of them with this post by saying that this is my go-to map. I will spend time just studying it, and it's still surprising to me what nuggets I can mine out of it.

Again, I know this won't be new to some of you, but I like being very open with what I do, and if someone out there can use this and continue (or add to) the research, then I'm all for it.

Anyway, the other half of this will be in the next day or so. I'll see you then, and as always...thanks for reading.

Thursday, August 29, 2019

A Room With A...Migraine

As you've probably already gathered, I don't always talk about chronology on here. I always mention it in some way, but it doesn't always apply to my subject each time. This is one of those times. I was skimming through The Canon a few days ago and saw something I thought might be interesting to see in a list/blog form. So, let's talk about it.

I was reading 'The Cardboard Box' (CARD) and saw the term dissecting-room. It then occurred to me that I'd seen another similar term in 'The Five Orange Pips' (FIVE) - lumber-room. So, an idea was born: how many different types of rooms are mentioned in the 60 cases? Well, I now know. (I also fear I'm going to make a few mistakes here because this gets a little confusing.)

There are the standards, of course - bedroom (bed room), dining-room, and bath-room. We have others that seem familiar, but may require just a hint of explanation - front room (or lounge or living room), so named because it was near the front of the home. Drawing-room (drawingroom) and sitting-room are actually interchangeable, and were also called withdrawing rooms. (These can also be interchanged for front room, but not as directly.) One could even use the term state-room here, but the difference in terms seems to have been a class or social status thing.

(A pretty standard Victorian sitting-room...if you had some money.)

The dressing-room is pretty self-explanatory, and eventually become the walk-in closet. Dressing-rooms had some furniture in Victorian times, but nowadays in a standard home you'd find a hamper or dresser, though I think the idea of having a room just for getting dressed is not as entrenched as it once was. (The amount of time required for a stately woman to get dressed back then was rather extensive, and I can see why it got more attention than it does today.)

Another one was the morning-room. Now, this one confuses me a bit, so I'm actually lifting an entire paragraph about it from a site ran by one Geri Walton. "A Morning-room was sometimes used as a Parlor or a “more homely Drawing-room.” Morning-rooms tended to be attached directly to Drawing-rooms and were used to relieve Drawing-rooms. In smaller residences, however, the Dining-room usually functioned as the Morning-room and in the evening that room might be superseded by a more formal Drawing-room." (Yeah, I still don't get it.)

(A Victorian drawing-room.)

Piggybacking off of that, I'm going to do the same with breakfast-room. "Breakfast-rooms or Luncheon-rooms were rooms used to serve breakfast or lunch. Breakfast-rooms were found in smaller homes, considered inferior to Morning-rooms, and differed from a Morning-room in that they possessed the character of a Parlor/Dining-room and not a Drawing-room. The Breakfast-room could also relieve the Parlor/Dining-room. Breakfast-rooms were usually attached to Dining-rooms or in close proximity to the Service-room. In small residences, a Breakfast-room might also serve as the family’s ordinary Dining-room." (Makes my head spin.)

Ante-room also appears in The Canon, as does waiting-room (waiting room)...and they're kind of the same thing. The dwelling-room is also called a great room, or fireroom (the room with the fireplace). The lumber-room was not what you think - a place for firewood or old lumber for the fireplace, but a room where excess furniture was stored. Meanwhile, the bar-room is fairly self-explanatory, as is billiard-room (billiard room), smoking-room, and gun-room.

(Probably only a standard billiards room if you were loaded.)

The consulting-room was for doctors or physicians, and housekeeper's room was actually a real name for the...well...housekeeper's room. A lodge room was a room in a lodge, and an engine-room was in a boat. And a dissecting room was in a hospital or amphitheater at a medical school.

Schoolroom needs no help, and a harness-room makes you think of horses...which is correct. A box-room (boxroom) was a term used to describe a small bedroom, and a greenroom is a theater word we've all heard. A strong-room (strongroom) was essentially a vault, a tap-room was a public bar, and a dryingroom was just that - a room for drying clothes.

Now, most of these terms have secondary and tertiary meanings, and can be interchanged with each other and other descriptive words depending on a lot of factors. From a chronological standpoint, one could spend a lot of time researching each of them, finding out the history of their usage and popularity. Once you had all of that, you could apply it to the tricky Sherlockian timeline. Perhaps someone has to a certain degree, but I don't think there's a one-stop shop for it. (I'm not going to say I want to, but I know I'm the kind of person who would.)

One of the hardest things about putting this post together was finding period-correct photographs to use. I was kind of surprised at how many there AIN'T! But, I think I did okay.

September is soon upon us, and we'll keep things going here at Historical Sherlock headquarters. I'll see you on Facebook, and right back here next month. Ta-ta until then, and as always...thanks for reading.

I was reading 'The Cardboard Box' (CARD) and saw the term dissecting-room. It then occurred to me that I'd seen another similar term in 'The Five Orange Pips' (FIVE) - lumber-room. So, an idea was born: how many different types of rooms are mentioned in the 60 cases? Well, I now know. (I also fear I'm going to make a few mistakes here because this gets a little confusing.)

There are the standards, of course - bedroom (bed room), dining-room, and bath-room. We have others that seem familiar, but may require just a hint of explanation - front room (or lounge or living room), so named because it was near the front of the home. Drawing-room (drawingroom) and sitting-room are actually interchangeable, and were also called withdrawing rooms. (These can also be interchanged for front room, but not as directly.) One could even use the term state-room here, but the difference in terms seems to have been a class or social status thing.

(A pretty standard Victorian sitting-room...if you had some money.)

The dressing-room is pretty self-explanatory, and eventually become the walk-in closet. Dressing-rooms had some furniture in Victorian times, but nowadays in a standard home you'd find a hamper or dresser, though I think the idea of having a room just for getting dressed is not as entrenched as it once was. (The amount of time required for a stately woman to get dressed back then was rather extensive, and I can see why it got more attention than it does today.)

Another one was the morning-room. Now, this one confuses me a bit, so I'm actually lifting an entire paragraph about it from a site ran by one Geri Walton. "A Morning-room was sometimes used as a Parlor or a “more homely Drawing-room.” Morning-rooms tended to be attached directly to Drawing-rooms and were used to relieve Drawing-rooms. In smaller residences, however, the Dining-room usually functioned as the Morning-room and in the evening that room might be superseded by a more formal Drawing-room." (Yeah, I still don't get it.)

(A Victorian drawing-room.)

Piggybacking off of that, I'm going to do the same with breakfast-room. "Breakfast-rooms or Luncheon-rooms were rooms used to serve breakfast or lunch. Breakfast-rooms were found in smaller homes, considered inferior to Morning-rooms, and differed from a Morning-room in that they possessed the character of a Parlor/Dining-room and not a Drawing-room. The Breakfast-room could also relieve the Parlor/Dining-room. Breakfast-rooms were usually attached to Dining-rooms or in close proximity to the Service-room. In small residences, a Breakfast-room might also serve as the family’s ordinary Dining-room." (Makes my head spin.)

Ante-room also appears in The Canon, as does waiting-room (waiting room)...and they're kind of the same thing. The dwelling-room is also called a great room, or fireroom (the room with the fireplace). The lumber-room was not what you think - a place for firewood or old lumber for the fireplace, but a room where excess furniture was stored. Meanwhile, the bar-room is fairly self-explanatory, as is billiard-room (billiard room), smoking-room, and gun-room.

(Probably only a standard billiards room if you were loaded.)

The consulting-room was for doctors or physicians, and housekeeper's room was actually a real name for the...well...housekeeper's room. A lodge room was a room in a lodge, and an engine-room was in a boat. And a dissecting room was in a hospital or amphitheater at a medical school.

Schoolroom needs no help, and a harness-room makes you think of horses...which is correct. A box-room (boxroom) was a term used to describe a small bedroom, and a greenroom is a theater word we've all heard. A strong-room (strongroom) was essentially a vault, a tap-room was a public bar, and a dryingroom was just that - a room for drying clothes.

Now, most of these terms have secondary and tertiary meanings, and can be interchanged with each other and other descriptive words depending on a lot of factors. From a chronological standpoint, one could spend a lot of time researching each of them, finding out the history of their usage and popularity. Once you had all of that, you could apply it to the tricky Sherlockian timeline. Perhaps someone has to a certain degree, but I don't think there's a one-stop shop for it. (I'm not going to say I want to, but I know I'm the kind of person who would.)

One of the hardest things about putting this post together was finding period-correct photographs to use. I was kind of surprised at how many there AIN'T! But, I think I did okay.

September is soon upon us, and we'll keep things going here at Historical Sherlock headquarters. I'll see you on Facebook, and right back here next month. Ta-ta until then, and as always...thanks for reading.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)